London – Hammersmith

Hammersmith’s first recognition as a renal centre came from its studies on Crush Syndrome (rhabdomyolysis) in the second world war, and subsequent development of methods for managing acute renal failure without dialysis. These were primarily clinical projects followed by laboratory studies.

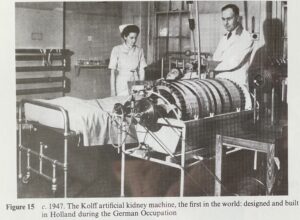

In 1946 they received one of Wilhelm Kolff’s rotating drum kidneys from Holland, publishing their results in 1948. Over the following decade it was the only centre able to perform dialysis, but with the development of conservative management methods it was scarcely used until a new machine in 1957. See also

In 1946 they received one of Wilhelm Kolff’s rotating drum kidneys from Holland, publishing their results in 1948. Over the following decade it was the only centre able to perform dialysis, but with the development of conservative management methods it was scarcely used until a new machine in 1957. See also

In the 1970s Keith Peters oversaw a blossoming of laboratory and clinical research in the department at Hammersmith around complement, anti-GBM disease, vasculitis, and clinical immunology. In the next decades it remained one of the UK’s major renal centres, and through amalgamation with Charing Cross and St Mary’s Hospitals became the largest renal unit in the UK.

Contents

ARF (AKI) in the 1940s and 50s

Crush syndrome

During the bombing of British cities in the early part of the second world war, from September 1940, ‘crush syndrome’ became recognised in those recovered alive from under rubble. Eric Bywaters, a rheumatologist at Hammersmith, described a series of fatal cases in 1941, and went on to identify myoglobin as the nephrotoxin that caused it, leading to a recommended management strategy.

- More at 1940s: Discovering AKI

Conservative management of oliguric ARF

Graham Bull came to Hammersmith from South Africa in 1947, taking over the renal service in the same year when Bywaters left, and after the initial experience with dialysis (below). His name is associated with the protein-free, calorie rich diet that was part of the conservative regimen that he developed with Ken Lowe and Jo Joekes – the ‘Bull diet’ published in 1949. This work had a huge influence, but the team had a short life; Bull went to Belfast as professor of Medicine in 1952 (Bull on Wikipedia) when he was succeeded by Malcolm Milne, Lowe went to Dundee the same year, and Joekes to St Mary’s soon after.

- More at 1940s: Discovering AKI

Experiments with dialysis

In 1946 Hammersmith received one of Wilhelm Kolff’s rotating drum kidneys from Holland, pictured above. The initial contact was Dr Jo Joekes, who seems to have undertaken the major part in using it, and who took his dialysis expertise subsequently to RAF Halton and the Middlesex Hospital. Their results were published in 1948, ostensibly positive, but subsequent comments at meetings and in publications make their doubts apparent: huge effort and manpower was required to make the machine work safely and effectively, and intensive conservative management was seeing successes and became the focus of research.

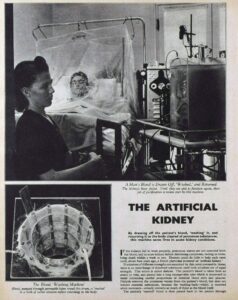

Over the following decade conservative approaches were refined used almost exclusively in the UK, although it seems that dialysis was used very occasionally still at Hammersmith – the only centre in the UK able to perform it after 1948/49. Interestingly, an article in the 8 April 1950 edition of Picture Post seems to show a different dialysis machine with similarities to Gordon Murray’s machine in Toronto, but presumably made locally.

Over the following decade conservative approaches were refined used almost exclusively in the UK, although it seems that dialysis was used very occasionally still at Hammersmith – the only centre in the UK able to perform it after 1948/49. Interestingly, an article in the 8 April 1950 edition of Picture Post seems to show a different dialysis machine with similarities to Gordon Murray’s machine in Toronto, but presumably made locally.

- More on AKI in the 1940s

Film of dialysis at Hammersmith in 1957

Film of dialysis at Hammersmith in 1957

In 1956, Ralph Shackman, a urologist seeking to support his planned transplant programme, with Malcolm Milne, purchased and operated a French (Necker-Usifroid) version of the Boston-modified Kolff rotating drum kidney, shown in operation in the adjacent linked video. A much better experience treating 14 patients was described (1957).

Milne led the renal service 1952-61 before going to Westminster as Professor of Medicine. Milne, a very highly regarded clinician and researcher, may have modified his thinking about dialysis when Belding Scribner visited in 1956, but his greater interests were in physiology, rather than managing uraemia. Nevertheless Shackman and Milne coauthored a paper describing their experience with some enthusiasm in 1958. Dialysis remained under the control of urologists until [????].

Long term dialysis

The new dialysis unit, c1966/67

The new dialysis unit, c1966/67

A long term dialysis programme was established only in 1966. For many years this remained under the control of the urology team. Recollections describe the sometimes slightly ornamental methods that the renal registrar had to employ to ‘sell’ patients to be accepted by the urology team, including imaginative methods to escape perceived biases.

Photo: two patients dialysing with twin coil kidneys in a shared dialysate bath? (Date unknown.) At this time PD was also employed for acute renal failure, and IPD as a temporary/ medium term treatment pre-transplant, and if there was inadequate capacity for haemodialysis (see 1950s: acute dialysis).

Transplantation

Ralph Shackman performed the first Hammersmith transplant in 1961(?), but there was a substantial prior history of laboratory work on transplantation and the nature of rejection at Hammersmith. This was successful and influential. The highly able Professor of Surgery Iain Aird was interested in the possibilty of transplantation, and engaged Jim Dempster (an Edinburgh University contemporary of Sheila Sherlock) to undertake studies in transplantation in dogs, working at Down House (previously home of Charles Darwin) and Buckston Browne Farm. Dempster moved from transplantating to the neck to the bladder, and identified acute rejection occurring at 10-15 days with accelerated (48h) rejection if retransplanted. Other work included analysis of the nature of rejection; graft versus host disease; and the immunosuppressive effect of irradiation.

As in other centres at this time, the earliest clinical accounts describe mostly failure, from inadequate or over-immunosuppression. Dempster had assisted with an unsuccessful transplant at St Mary’s early on, that he later described as futile.

- John Hopewell’s account of UK Transplantation gives additional detail

- Hammersmith timeline, additional info, and references

1970 to 1990s research advances

Shortly after his appointment as lecturer in 1970 Keith Peters established laboratory research into the immunology of nephritis and (with Peter Lachmann) into complement in nephritis. Many future academic and clinical leaders passed through the lab and service during his time there, and subsequently.

- Anti-GBM disease – key clinical and experimental observations and progress.

- Complement – Keith Peters describes work on complement.

- Vasculitis – introduction of ANCA assays, management protocols, and study of cell biology and pathogenesis.

- Other work on glomerular diseases

Further info

- Hammersmith timeline, further detail, and references

- Michael Boulton Jones view as senior registrar 1972-75

Images are from Calnan 1985, The First 50 Years

Authorship

First published April 2025

Last Updated on October 20, 2025 by neilturn