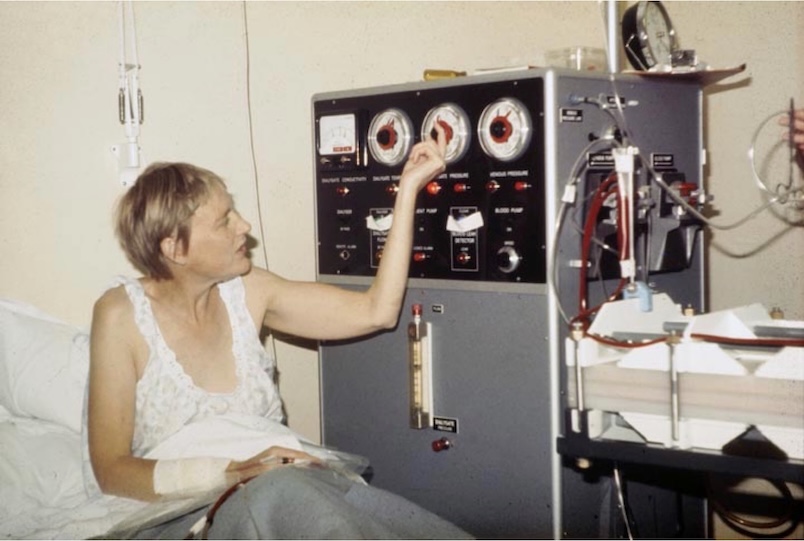

Jean Tarver

Image shows Jean learning to operate a Lucas dialysis machine for home treatment in 1967

Oxford’s first long-term dialysis patient

No doubt many staff in dialysis units remember their first patient, but most are probably now dead and their nephrologists retired. The first Oxford patient was remarkable in that she survived continuous dialysis for 35 years, never had a transplant and outlived the physician (three years younger than she) who saved her life. At his funeral, she sat at the front of the church in her wheelchair, accompanied by her middle-aged son, who was 12 years old when she started treatment.

Contents

UK renal services in 1966

Jean’s story hints at a national challenge to provide dialysis for end stage kidney failure. This expensive but exciting lifesaving technological new treatment led to a break away from regional funding and decision making. Oxford was one of the ten units that received central government funding to establish a limited number of patients on dialysis in the mid 1960s, but Jean needed treatment before the first, limited Oxford facilities became available.

Reaching kidney failure, and its politics

Jean’s illness began in April 1953 when she was 26. She presented with Henoch–Schönlein purpura six months after her first, and only, pregnancy. High-dose cortisone was prescribed without benefit. The side-effects were so unpleasant that she had a lifelong abhorrence of them. The nephritis proved chronic and, in 1960, she developed accelerated phase hypertension with Grade IV fundal changes. The blood pressure was difficult to control with the few agents then available, and she progressed towards ESRF.

-

- 1964: blood pressure becomes treatable – the first drugs (historyofnephrology blog)

By November 1966, she was in pulmonary oedema, with pericarditis and seizures. She was under the care of the then Regius Professor of Medicine, Sir George Pickering, an international authority on high blood pressure (he apparently quibbled with the term ‘hypertension’), but who had no special interest in renal disease or renal failure. Although dialysis was available elsewhere in the country, he advised palliative care using Brompton’s Mixture – a combination of chlorpromazine and diamorphine.

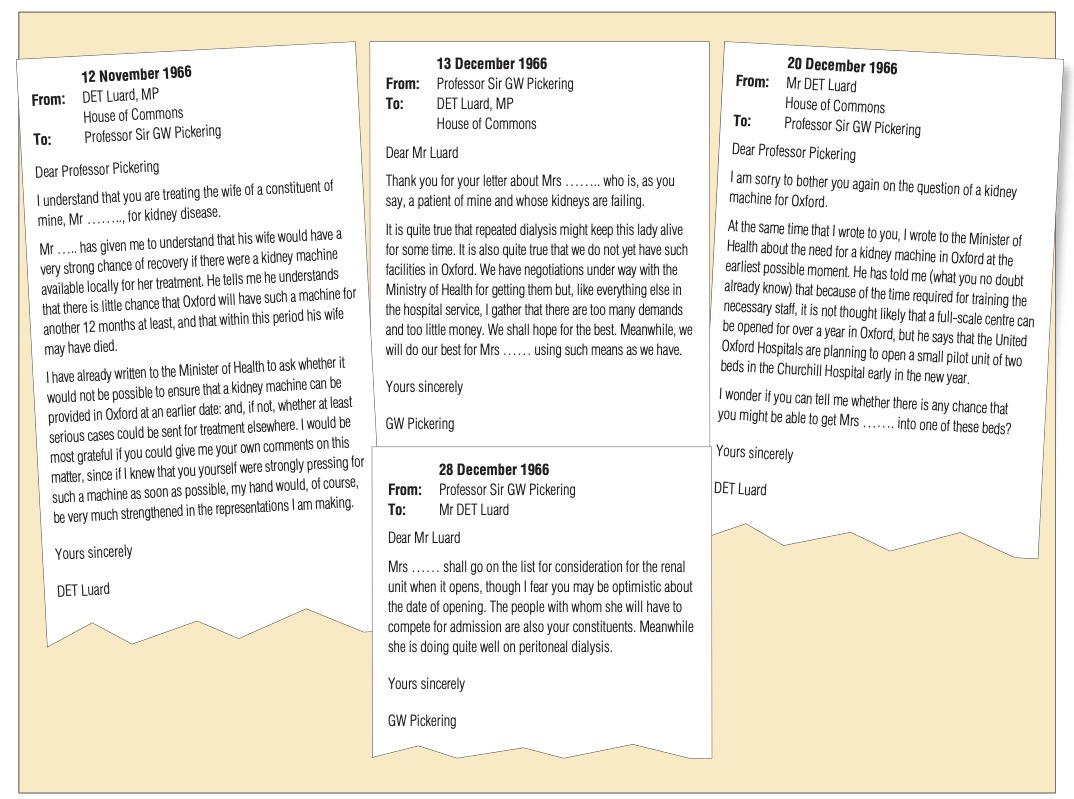

Jean was married to John, a schoolteacher and secretary of the local Communist Party, who pressed his Member of Parliament about his wife’s plight. Her presentation with terminal renal failure became a crucial moment for Sir George who, by then, had been lobbied on her behalf by the MP, Mr DET Luard (Figure 1, opposite).

Time was bought by Sir George’s ‘first assistant’ (senior registrar [resident] in later parlance), Dr Desmond Oliver, a New Zealander who had come to England to gain postgraduate experience. He had worked first in the Royal Postgraduate Medical School at Hammersmith Hospital for Professor Oliver Wrong, where he had learnt the technique of peritoneal dialysis (PD). This was mostly used on patients with acute renal failure, but sometime and less satisfactorily as intermittent peritoneal dialysis (IPD) to keep patients alive before renal transplantation. Dr Oliver initiated IPD on Jean, which continued until August 1967. This was not without incident – on one occasion, an error in making up the PD solution resulted in her receiving 3,000 ml of a very hypertonic dialysate. As a result, she was described as having cerebral dehydration and had a grand mal convulsion. She was rescued with intravenous 5% dextrose and PD was recommenced ‘with a new solution’.

A Quinton–Scribner shunt was inserted (the first having been used in March 1960 in Seattle by Scribner), allowing haemodialysis using a coil dialyser (Chron-a-coilTM) and a Baxter single-pass recirculation tank machine. This was started on 8 August 1967. The Discharge Summary that was sent to her family doctor described, ‘Excellent control of uraemia, but unfortunately frequent transfusions are required’. By the end of that year, a Lucas machine and Kiil dialysers became available and her transfusion requirements diminished. This lobbying on Jean’s behalf may have contributed to Oxford being chosen as one of the pilot sites for a regional haemodialysis service in the UK. Dr Desmond Oliver was appointed to a new NHS post to set up the programme, and was given a prefabricated building for the four dialysis stations. That building, due for demolition even then, is still standing and houses the administration of a programme that has expanded beyond the politicians’ worst nightmares. It was agreed at the beginning that dialysis would be offered only to patients who were deemed ‘suit- able for renal transplantation’, or who were able to undertake treatment at home, and that the hospital stations were to be used for training and respite care only. This principle was defended until 1981, when home haemodialysis failed, patients whose transplants failed refused to return home, and there was a growing number of marginal candidates to whom chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) had been offered and in whom it had failed. Gradually, more such patients occupied the hospital stations.

This lobbying on Jean’s behalf may have contributed to Oxford being chosen as one of the pilot sites for a regional haemodialysis service in the UK. Dr Desmond Oliver was appointed to a new NHS post to set up the programme, and was given a prefabricated building for the four dialysis stations. That building, due for demolition even then, is still standing and houses the administration of a programme that has expanded beyond the politicians’ worst nightmares. It was agreed at the beginning that dialysis would be offered only to patients who were deemed ‘suit- able for renal transplantation’, or who were able to undertake treatment at home, and that the hospital stations were to be used for training and respite care only. This principle was defended until 1981, when home haemodialysis failed, patients whose transplants failed refused to return home, and there was a growing number of marginal candidates to whom chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) had been offered and in whom it had failed. Gradually, more such patients occupied the hospital stations.

Home dialysis begins – 1968

As Jean’s husband was a schoolteacher, the Teachers’ Benevolent Fund of the National Union of Teachers offered to help with the purchase of a dialysis machine for use at home. Jean was considered suitable for home haemodialysis and so a Lucas machine was ordered, but in the end it was paid for by the NHS. Delicate negotiations were conducted to find alternative accommodation for Jean’s mother-in-law, who lived in the family home. The headmaster of the school at which her husband taught agreed to excuse him from teaching some classes so he could learn to assist his wife. By the Easter of 1968, Jean was the fourth patient to be successfully established on home dialysis (Figure 2). Her husband was her helper, but her son helped to build the Kiil dialyser and was ‘on call’ when his father went out. Apart from the ten hours of actual treatment, building the Kiil dial- yser was time-consuming and frustrating. It took two hours to set the machine up and about one and a half hours to clean up after the ten-hour treatment. One had to start again if it leaked. Jean spent about 40 hours per week on dialysis.

In her routine follow-up letters, Jean was reported to be well enough to manage all her housework, look after her now incapacitated mother-in-law and do some voluntary work in the hospital. By 1970, however, she had become depressed and required admission for respite hospital haemodialysis. Later that year, she underwent a total parathyroidectomy, and her shunt required its first revision. (Although the Brescia–Cimino fistula was described at the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs meeting in April 1966, the technique was not immediately adopted in Oxford. Eventually, a plastic surgeon undertook the procedure on later patients.) There was no renal transplant programme in Oxford, so patients were referred to either Cambridge or Birmingham. The early results with transplantation were disappointing and Jean declined referral, deciding to stick with what she knew. Even when Professor Peter Morris started the Oxford programme in 1975, she remained reluctant – mostly because of her horror at the thought of having to be on high-dose corticosteroids again.

Jean’s medical history over the next 30 years is a catalogue of all the complications of long-term haemodialysis (Table 1). Despite this, she trained as a secretary and worked in the Applied Social Science section of Ruskin College, Oxford, from 1975 until she retired in 1987. When her marriage failed in 1975, home haemodialysis was maintained by taking in a student lodger, who acted as her assistant until her son could take on the role.

In 1978, she was found to be iron-overloaded, a result of the well-intentioned but misguided policy of administering large doses of iron dextran to all haemodialysis patients. In that same year, she was one of the first beneficiaries of vitamin D analogues given to treat renal bone disease, by participating in studies of alfacalcidol (‘One-Alpha’) being run by drs (later professors) John Kanis and Tim Cundy.

Table 1. A timeline of events during Jean’s dialysis career

| Year | Yrs since ESRF | Age | Event |

| 1966 | 39 | Terminal renal failure/ intermittent PD | |

| 1967 | 1 | 40 | Starts haemodialysis |

| 1968 | 2 | 41 | Home haemodialysis |

| 1970 | 4 | 43 | Depression |

| 1970 | 4 | 43 | Parathyroidectomy |

| 1978 | 12 | 51 | Iron overload |

| 1978 | 12 | 51 | Starts alfacalcidol |

| 1986 | 20 | 59 | Dialysis amyloid |

| 1987 | 21 | 60 | Starts r-HuEPO |

| 1988 | 22 | 61 | Carpal tunnel syndrome |

| 1991 | 25 | 64 | Breast cancer |

| 1996 | 30 | 69 | Cervical cord compression |

| 1997 | 31 | 70 | Basal cell carcinoma |

| 2000 | 34 | 73 | Polymyalgia rheumatica |

| 2001 | 35 | 74 | Brainstem stroke and death |

Back to hospital dialysis – 1985

Eventually, in 1985, home treatment had to be abandoned and Jean had to have her dialysis in the main unit, breaking the diktat of that time that no patient should rely on hospital-based treatment. She was supervised by Desmond Oliver, assisted by an impressive team of nurses, dialysis technicians and a succession of registrars who have gone on to make their marks in nephrology and science elsewhere. (Table 2, see below). She was handled with special care because she was known to ‘have the ear of the director’ and could rapidly discern whether the new doctor knew what he was talking about. In a sense, she helped to train them all.

In 1986, Jean required a left total hip replacement and the pathology was confirmed as beta 2 microglobulin dialysis amyloid (first described in 1982). Two years later, in 1988, when she had been on dialysis for 22 years, she required her first carpal tunnel releases for the same pathology. The previous year (1987) she entered one of the pioneering AMGEN/Ortho Biotech Oxford trials of recombinant human erythropoietin, solving a problem that had limited her life for over two decades. The progressive and devastating effects of dialysis amyloidosis persuaded many of Oxford’s now over 100 home haemodialysis patients to put themselves forward for renal transplantation, but sadly Jean developed a carcinoma of the breast in 1991 and this option was felt to be contraindicated. Her vascular access became an issue when, after an amazing 20 years of managing with Quinton–Scribner shunts that required intermit- tent venous and arterial revisions, she ran out of veins. A brachial arteriovenous fistula served her for a while, but this had to be converted to a Goretex™ graft and when this clotted she settled for Tesio twin catheter access via her subclavian vein, which lasted her the remainder of her dialysis life.

1996 brought the most serious threat to Jean’s health, morale and independence. Dialysis amyloidosis had caused cervical cord compression at C6 and C7. The neurosurgeons successfully fused the vertebrae and she recovered to continue living at home, albeit wheelchair- bound. In 2000, she required a prolonged admission for a fever and malaise attributed to infection of her access, but never proven; eventually the penny dropped – she had polymyalgia rheumatica – reminding her nephrologists that dialysis patients are not immune to other diseases. She benefited dramatically from the corticosteroids she had spent so many years trying to avoid. In 2000, her quality of life was poor and independence at home was looking more difficult to sustain (she vowed not to live in a nursing home). In November 2001 she had a fall and, while waiting for surgery to her soft tissue injury, lapsed into a coma – probably the result of a brainstem stroke. She came back to the kidney unit to be nursed. On her final ward round, the only person who had been alive in the year that she started haemodialysis was the consultant, Dr Winearls, who had been in his last year at school. She died peacefully without regaining consciousness.

Jean had had about 5,000 haemodialyses, countless surgical procedures and her four volumes of notes weighed 8 kg at the time of her death. Why did she do so well? She was very compliant with treatment, dialysing for long hours (eight to ten hours three times a week in the early years), had an excellent blood pressure, well-controlled phosphate concentrations and modest interdialytic fluid gains. Although she became curmudgeonly toward the end, she never allowed herself the luxury of self-pity. Her medical and surgical care was obsessional, not least because she insisted that it be so. She is among the longest-surviving renal failure patients who never had a transplant.

Table 2. Consultant nephrologists whose registrar training included care of Jean 1966–2001

| Name | Institution |

| 1960s | |

| Dr Farrokh Wadia | Poona, India |

| Prof George Nicholson | Barbados, West Indies |

| 1970s | |

| Prof Dwomoa Adu | Queen Elizabeth II Hospital, Birmingham, England |

| Dr RG Henderson | Hinchingbrooke Hospital, Cambridge, England |

| Dr Michael Pascoe | Cape Town, South Africa |

| Prof Raman Gokal | Manchester Royal Infirmary, Manchester, England |

| Prof Laurence Chan | Denver, USA |

| Dr Chris Winearls | Oxford, England |

| Prof Anthony Raine | St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, England |

| 1980s | |

| Prof Peter Ratcliffe | Oxford, England |

| Prof Stephen Reeders | Yale, USA |

| Prof Stephen Sacks | Guy’s Hospital, London, England |

| Dr Fernando Fervenza | Mayo Clinic, Rochester, USA |

| Dr John Firth | Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge, England |

| Prof Christopher Pugh | Oxford, England |

| Dr Jeremy Chapman | Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia |

| Prof Bruce Hendry | King’s College, London, England |

| 1990s | |

| Dr Christopher Dudley | Bristol, England |

| Dr Lawrence McMahon | Royal Melbourne Hospital, Australia |

| Dr Ashley Irish | Royal Perth Hospital, Perth, West Australia |

| Dr Grant Flanagan | Victoria, Australia |

| Dr Robyn Langham | Sydney, Australia |

| Prof Patrick Maxwell | Imperial College, London, England |

| Dr Jonathan Gleadle | Oxford, England |

Acknowledgements

This article was originally posted in the British Journal of Renal Medicine in 2003. It is reproduced here with minor alterations by kind permission of Hayward Medical Publishing (PMG Group).

Mrs Margaret Miller (née Paul) [Dialysis Unit Sister 1967–1988], Norman Torgersen (Dialysis Technician in 1967), Mrs Sheila Oliver (widow of Desmond Oliver), Professor J Stewart Cameron, and Jean’s son all made constructive criticisms of the manuscript. The authors would also like to thank Jean’s son for his permission to publish this article.

Authorship

First posted 15 Nov 2025

Last Updated on November 17, 2025 by neilturn