IgA Nephropathy Research in Leicester 1982-2010

by John Feehally

Contents

- Why study IgA nephropathy?

- Why IgA Nephropathy?

- Manchester

- Leicester

- Is the control of IgA production abnormal in IgAN?

- From where in the IgA immune system is the deposited mesangial IgA derived?

- Why does IgA deposit in the mesangium in IgAN but not in healthy subjects?

- Why is IgA1 glycosylation different in IgAN?

- Who else was studying IgA glycosylation?

- Why are complement components co-deposited with IgAN in IgAN?

- Is there a genetic predisposition to IgAN or its progression?

- IIgANN – International IgA Nephropathy Network

- Oxford Classification of IgAN

- Treatment of IgAN

- Succession planning

Why study IgA nephropathy?

I became properly interested in IgA nephropathy in 1982 when, after my registrar job in Leicester, I began a research fellowship in Manchester with Netar Mallick and Paul Brenchley. I had gone there because I wanted to study human glomerular disease in humans, rather than engaging with experimental models designed (although often inadequately) to reprise human disease.

IgAN had caught my attention as a fledgling nephrologist from the time I first saw cases being presented at the renal biopsy meetings in Bristol where I was an SHO, and then as a registrar in Leicester.

I was already drawn to the study of glomerular disease from the time I spent three months in paediatrics in 1978 as SHO to George Haycock in Bristol (he was soon to move to Guy’s) and he taught me the clinical approach to nephrotic syndrome in children. He also taught me to read all I could find written by Stewart Cameron.

Why IgA Nephropathy?

Through the murk of more than forty years it is hard to be sure exactly why IgAN (of all the patterns of glomerular disease) caught my attention and grabbed me with such powerful clutches that it became the main focus of my research efforts until I retired.

I suspect it was a combination of some or all of the following challenges and opportunities:

- IgAN was a new disease, it was barely a decade since it had been first described by Jean Berger in Paris.

- Its clinical features and natural history were only just being characterised.

- It was beginning to seem common and disproportionately affecting young males, sometimes causing kidney failure in the prime of life.

- Very few groups worldwide were studying it.

- The literature was slim, so it would be possible to read and assimilate it all in quite a short time.

- It would not be easy to establish animal models which properly reprised the human disorder, satisfying my interest in direct study of glomerular disease in humans.

- IgAN was already raising some interesting questions.

- Why did some but not others develop progressive renal failure?

- Why did episodes of visible haematuria coincide with mucosal infection?

- Why did some with IgAN also get a systemic vasculitis (known at that time Henoch-Schnlein purpura)

- Polymeric IgA1 (pIgA1) was the molecular IgA species characteristic of the mesangial IgA in IgAN, but why was this?

Manchester

Arriving in Manchester we soon agreed that IgAN studies would be one part of my DM thesis (I also studied membranous nephropathy and minimal change nephrotic syndrome).

We read the existing slim literature, mostly derived from cross sectional association studies in which serum (and rarely urine) samples were analysed seeking factors associated with IgAN. As yet there was virtually no longitudinal sampling which might reveal factors associated with risk of progression, nor had there been any studies of acute samples, collected for example during episode of visible haematuria. The latter was a logistic challenge which was important to overcome.

So, in Manchester we assembled a cohort of young adults and children with IgAN who had previously had one or more episodes of visible haematuria, and waited patiently for it to happen again, so we could sample them acutely. It happened enough times during my two year fellowship to provide the basis for my first paper in KI (eventually published two years after I left Manchester). Critical to this study was the support of the adult glomerular disease clinic at Manchester Royal Infirmary (under the day-to-day supervision of Colin Short) and also the enthusiastic facilitation at Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital of Bob Postlethwaite, paediatric nephologist, and his senior registrar, Jim Beattie (later consultant in Glasgow). The geographical practicalities were left to me to solve, and I was regularly found chugging across Manchester on a moped with a panier full of fresh blood samples from children requiring immediate analysis.

We found that during haematuric episodes provoked by URTI there was an increase in circulating polymeric IgA which was prolonged and exaggerated compared to controls, and that the in vitro production of IgA by circulating B cells was also exaggerated (Feehally J et al. Sequential study of the IgA system in relapsing IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int 1986; 30: 924-931).

The control of IgA production was not normal, but what did this mean?

Towards the end of my time in Manchester I attended with Netar and Paul in 1983 the Second International Symposium on IgA Nephropathy in Milano, Italy. This confirmed my view that very little was known about IgAN, and I also began to make the friendships which helped make later international collaborative work on IgAN so successful.

Leicester

Arriving back in Leicester in 1984 as a lecturer, and as it turned out to remain there as a consultant for the rest of my career, I fixed on IgAN as a long-term research challenge. A start had been made but if we were to progress our understanding of the pathogenesis of IgAN we would need to refine the questions we hoped to answer, and develop more precise investigative tools.

Over the next three decades we set out to answer these key questions:

- How is the control of IgA production abnormal in IgAN?

- From where in the IgA immune system is the deposited mesangial IgA derived?

- Why does IgA deposit in the mesangium in IgAN but not in healthy subjects?

- Why was visible haematuria coincident with mucosal infection?

- Is there a genetic predisposition to IgAN or its progression?

Several strategic decisions underpinned our efforts from the beginning:

- Our studies would all need to be in humans. Although others were enthusiastically developing rodent models with mesangial IgA deposits, I remained unconvinced that these bore useful resemblance to human IgAN, not least because the IgA immune system in rodents is so different from man. Eventually perhaps it might be possible to manipulate mice to ‘humanise’ the IgA system but in the 1980s this was a remote and high-cost prospect.

- We needed a cohort of cases with sequential longitudinal clinical data, and a matching biorepository of serum, urine, and biopsy samples.

- We needed to earn the respect and trust of patients in that cohort, to ensure strong recruitment to our studies.

- We needed to use the simplest possible appropriate techniques since our physical infrastructure (one bench in a small lab with limited kit) and our human resources (one part-time lab technician) were modest, and at first we had very little grant income. (Remarkably John Walls when negotiating with the hospital the salary and support for the second consultant post to which I was appointed had convinced the hospital to include this part time research salary – unthinkable in today’s financial climate in the NHS!) Lorna Layward was the first scientist who joined us in 1989, followed by Alice Allen (after her marriage, Alice Smith), who was a leader of our lab effort for some twenty years.

- And most importantly as money became available I needed to recruit people who were better than me at all the important things.

So, we set off.

Is the control of IgA production abnormal in IgAN?

Our hypothesis at this stage was that a hyperresponsive mucosal IgA system resulted in excessive pIgA1 in the circulation reaching the kidney. Having found that increased IgA1 levels were restricted to the serum and not found in saliva (Layward L et al . Elevation of IgA in IgA nephropathy is localized in the serum and not saliva and is restricted to the IgA1 subclass. Nephrology Dial Transplant 1993; 8: 25-28), we turned to immunisation studies. Systemic immunisation provoked an exaggerated IgA response in both mucosal and systemic compartments. A ‘natural’ immunisation experiment proved very interesting: Jonathan Barratt (soon after he joined us in 1996) studied subjects known to be mucosally infected with H.pylori and found that those with IgAN had an exaggerated circulating pIgA1 response (Barratt J et al. Exaggerated systemic antibody response to mucosal Helicobacter pylori infection in IgA nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 1999; 33: 1049-1057). We were gathering indirect evidence that the mucosal and systemic IgA systems are disordered in IgAN and perhaps the normal crosstalk between them was impaired.

But we still suffered from the weakness that we were working on circulating IgA without knowing where in the IgA system it had been synthesised and relying on the study of circulating IgA- producing cells, whose origin and fate were uncertain. We needed better approaches and Arvind Batra, a post-doc scientist, joined us to explore homing receptor expression on circulating T cells. He found an increase in the circulation of an activated subset of CD4 T cells, which carried the homing receptor for systemic rather than mucosal effector sites (Batra A et al. T-cell homing receptor expression in IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant 2007; 22: 2540-2548).

The next step was to study control of systemic IgA production more directly and make use of samples of bone marrow and duodenal mucosa already being collected by Steve Harper (see below). Alice Allen working with Colleen Olive and Michael Falk in Brisbane showed altered T cell patterns in mucosa with reduced numbers of γδ T cells expressing the variable region Vγ3 (Olive C et al. Expression of the mucosal gd T cell receptor V region repertoire in patients with IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int 1997; 52: 1047-1053) , a population known to be important for control of mucosal pIgA1 production. Kate Buck showed that the same γδ T cell population is diminished in the marrow in IgAN KS Buck et al. Expression of T cell receptor variable region families by bone marrow gd T cells in patients with IgA nephropathy. Clin Exp Immunol 2002;127(3):527-532).. These results deserve the epithet ‘intriguing’, but we never succeeded in developing achievable experiments which would enable us properly to unravel the role of disordered T cell function in the pathogenesis of IgAN. Not least because we had other questions to answer which were our greater priority.

From where in the IgA immune system is the deposited mesangial IgA derived?

To answer this, first we needed ethics approval and participant consent to undergo bone marrow aspiration and duodenal biopsy. Second, we had to develop techniques suitable for these tissues to identify cells producing IgA, and in particular cells producing pIgA.

Steve Harper (as a Wellcome Fellow) achieved these two aims – the second by collaboration with Howard Pringle in the Department of Pathology in Leicester who had developed in situ hybridisation (ISH) techniques suitable for tissue specimens.

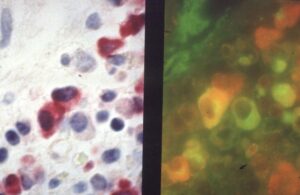

Steve’s beautiful and precise in situ hybridisation distinguishing cells producing only IgA (red), only J-chain, which is necessary for assembly of monomer IgA into pIgA from (green), , and cells producing both IgA and J-chain (red & green together appearing orange)

This work received recognition not least because no other group had thought that direct sampling of marrow and mucosa could be achieved in a research protocol. That patients were willing to participate was tribute to the relationships we built with them, earning their trust, and explaining with care our research goals.

It also taught us what Steve whimsically called ‘Feehally’s law’. Our hypothesis was that there would be excessive production of pIgA in the mucosa, which would be the pathogenic IgA reaching the mesangium. When Steve reported to me his studies showing the complete opposite (i.e. reduced mucosal production of pIgA in mucosa in IgAN) (Harper SJ et al. Expression of J chain mRNA in duodenal IgA plasma cells in IgA nephropathy, Kidney Int 1994; 45: 836-844, I sent him off to repeat the experiment thinly veiling my criticism that he must have cocked it up by mis-labelling the specimens. Only when the second and the third time the result was the same did I finally acquiesce that our hypothesis was completely wrong; it was time to rethink. Feehally’s law -when the results seems completely wrong they are probably completely right… think again.

Steve went on to find in IgAN that there was increased pIgA production in both the bone marrow (Harper SJ et al. Increased dimeric IgA producing B cells in the bone marrow in IgA nephropathy determined by in situ hybridisation. J Clin Pathol 1996; 49: 38-42) and in tonsillectomy specimens (Harper SJ et al. Increased dimeric-IgA producing B cells in tonsils in IgA nephropathy determined by in situ hybridisation for J chain mRNA. Clin Exp Immunol 1995; 101: 442-448).

But we still needed to address a third question –

Why does IgA deposit in the mesangium in IgAN but not in healthy subjects?

We considered two possibilities:

Expression or behaviour of mesangial IgA receptors might be abnormal and favour IgA binding, and mesangial cell activation. This was a rather murky field with a range of opinion in the IgAN literature about which mesangial receptors bound IgA, and which were likely culprits. Jonathan Barratt had come to us in 1996 from Leeds with an MRC Clinical Training Fellowship and joined by scientist Karen Molyneux, they in due course found a novel IgA binding receptor in human mesangium. A preliminary report by 2000 (Barratt J et al. Identification of a novel Fc alpha receptor expressed by human mesangial cells.

Kidney Int 2000; 57; 1936-1948), was not followed by full characterisation until 2017 (Molyneux K et al. β1,4-galactosyltransferase 1 is a novel receptor for IgA in human mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2017; 92(6):1458-1468) , delayed in part because the work was technically challenging, in part because we were being diverted by other exciting progress.

There might be some structural abnormality of IgA1 in IgAN which predisposed it to mesangial deposition and mesangial cell activation.

Altered glycosylation of IgA1 turned out to be a critical abnormality, and Alice Smith takes all the credit for developing the ideas and pursuing the work to fruition.

The starting point was that she noted emerging interest in altered glycosylation of IgG in rheumatoid arthritis, and soon realised that glycosylation of IgA might well have functional significance in IgAN since IgA1 (almost exclusively the IgA species in the mesangium) has a heavily O-glycosylated hinge region which is absent in IgA2.

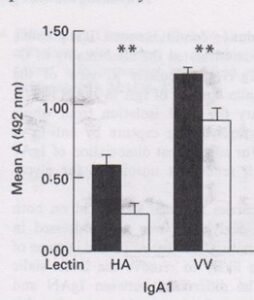

She found that the hinge region O-glycosylation could be detected using lectin binding in an ELISA system, and that serum IgA1 in IgAN did indeed have significantly altered O-glycosylation (Allen AC et al. Galactosylation of N- and O-linked carbohydrate moeities of IgA1 and IgG in IgA nephropathy. Clin Exp Immunol 1995; 100: 470-474). She went on to show this represented loss of terminal galactose exposing the O-linked sugars which bound the lectin.

Alice’s first published demonstration that binding of two different lectins to IgA1 was increased in IgAN (black) compared to controls (white).

Fortunately the ELISA findings correlated closely with more cumbersome direct methods such as stripping the glycans from IgA, separating them by electrophoresis, and visualising with a fluorophore (Allen AC et al. Analysis of IgA1 O-glycans in IgA nephropathy by fluorophore assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis. J Amer Soc Nephrol 1999; 10: 1763-1771).

This freed us to use lectin binding as a rapid assessment of IgA1 glycosylation on large numbers of samples.

We also took advantage of our partnership with Jim Beattie in Glasgow, who identified children with HSP, with or without nephritis, and we showed that only those with nephritis, had altered IgA1 O-glycosylation in the same pattern seen in IgAN (Allen AC et al. Abnormal glycosylation in Henoch-Schönlein purpura restricted to patients with clinical nephritis. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant 1998; 13: 930-934)

If we wanted to prove that altered glycosylation promoted mesangial deposition we must deal with the criticism that so far we had only measured glycosylation of circulating IgA, arguably a less important group of IgA1 molecules to study since the most abnormal molecules might already be trapped in the kidney.

In collaboration with Paul Brenchley we were able to source three complete IgAN kidneys which gave us ample material to elute glomerular IgA, and by lectin binding confirm in all three cases that the eluate was enriched for abnormally IgA glycosylated IgA (Allen AC et al. Mesangial IgA1 in IgA nephropathy exhibits aberrant O-glycosylation. Kidney Int 2001; 60:969-973).

It was beginning to look as though altered glycosylation was a very important pathogenic step. This of course raised the next question.

Why is IgA1 glycosylation different in IgAN?

Morag Greer showed the IgA1 hinge region amino acid sequence was not different in IgAN (Greer MR et al. The nucleotide sequence of the hinge region of IgA1 in IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant 1998; 13: 1980-1983)

Kate Buck found no difference in the marrow expression of β1,3 galactosyltransferase which adds terminal galactose to O-linked sugars, nor of its chaperone protein, Cosmc (Buck KS et al. B-cell O-galactosyltransferase activity, and expression of O-glycosylation genes in bone marrow in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int 2008; 73: 1128-36).

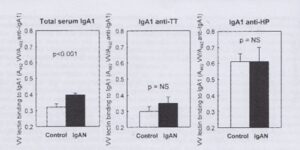

Then an important, though simple, experiment by Alice turned our thinking (Smith AC et al. Glycosylation of serum and mucosal IgA antibody responses in IgA nephropathy. J Amer Soc Nephrol 2006; 17: 3520-8).

Alice showed that IgA responses to mucosal antigens (in IgAN and in healthy controls) have a lectin binding glycosylation pattern which when seen in serum IgA1 in IgAN we have regarded as ‘abnormal’

Perhaps after all there is nothing wrong with the machinery of IgA1 glycosylation. It is simply that more mucosal type IgA is being produced in the marrow. Normal mucosal IgA but in the wrong place

Who else was studying IgA glycosylation?

There was only one other group – in Birmingham, Alabama. They had suggested that such an abnormality was plausible but it was Alice who was first to demonstrate it. They began a high cost, hi-tech, NIH-funded attempt to unravel IgA glycan abnormalities in IgAN. Inevitably we were reviewing each other’s papers – journal editors had few other well-informed referees to turn to. We began to see a shameless citation trick in action: in their papers they favoured the phrase ‘we and others have shown’…. and only ever cited their own work, usually review articles. They almost never referenced Alice’s original paper, and thus effectively air-brushed her primacy; the unsuspecting reader would presume this had all originated in Birmingham and never realise she had made the first report. Ah well……

Why are complement components co-deposited with IgAN in IgAN?

We had not yet addressed this question. We had not given it priority since conventional wisdom had it that IgA was a poor fixer and activator of complement.

Nick Medjeral-Thomas with Terry Cook at Imperial showed that C’ activation fragments were found in glomerular deposits and correlated with disease activity and severity (Medjeral-Thomas NR et al. Complement activation in IgA nephropathy. Semin Immunopathol. 2021 Oct;43(5):679-6900. This coincided with a new therapeutic phase for IgAN – since a range of complement inhibiting agents were coming to market, and Jonathan Barratt led the way nationally and internationally in treatment trials .

Is there a genetic predisposition to IgAN or its progression?

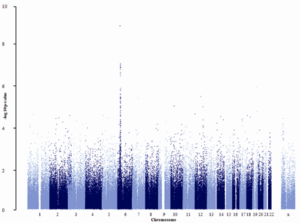

The world of molecular genetics was undergoing a technical revolution. The possibility was emerging to search the whole genome looking for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with disease. These genome-wide association studies (GWAS) were gaining increasing power as the density with which the chosen SNPs covered the genome was increasing, and it was becoming quicker and more affordable to scan large numbers of cases.

We were part of an MRC-funded UK consortium to make a DNA collection of cases with five common patterns of glomerular disease, of which one was IgAN. As soon as the collection was completed, we moved quickly (because a consortium in the USA was also moving quickly) to ensure we were able to present and publish in 2010 the first GWAS in IgAN, which identified disease associations with SNPs in HLA-DQ (Feehally J et al. HLA Has Strongest Association with IgA Nephropathy in Genome-Wide Analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 Oct;21(10):1791-7).

The first GWAS in IgAN (ref 20). A small study by GWAS standards (only ~900 subjects) – but a clear association with HLA-DQ genes on chromosome 6.

It was clear we could not continue to compete in this arena as the heavyweight forces of US biomedical funding and infrastructure built larger and larger cohorts, and we elected to contribute UK cases to that effort (Kiryluk K et al. Discovery of new risk loci for IgA nephropathy implicates genes involved in immunity against intestinal pathogens. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1187-96). Instead, we chose to refine questions and methods so we could answer specific genetic questions about IgAN using smaller study cohorts and richer datasets, work which Jonathan Barratt later took forward to great effect.

IIgANN – International IgA Nephropathy Network

Increasingly we were making our mark internationally. The ‘IgA Club’ was founded in the early 1980s by the senior leaders in IgAN research. When regular IgAN symposia began, the Club was little more than a list of e-mail addresses supporting a loose affiliation of friends and peers. With members of our small research group, I went to these biennial symposia regularly (I attended 10 of the 15 held between 1982 and 2018). Their narrow focus ensured that most if not all the active investigators in IgAN gathered there, and it was an excellent forum to test ideas and develop collaborations.

Discussion time at the International IgAN 25th Anniversary Symposium Nancy, France 1993. I remember the occasion well. Somewhat tactlessly, at the end of a session devoted to rodent models of IgAN, I had suggested all such efforts were useless because rodent IgA biology was so different compared to humans. This provoked a ‘lively’ discussion but happily some others agreed with me!

My friend, John Knight (paediatric nephrologist from Sydney) and I decided in 2005 to refresh and relaunch the IgA Club as the International IgA Nephropathy Network. We even had a logo designed:

A symbolic depiction of the pIgA molecule – the curved heavy chains and short light chains of two IgA molecules with the horseshoe-shaped J-chain molecule binding them together. The logo was drawn by John Knight’s son, Jasper, then a fledgling artist, now with an established international reputation across Australasia and Asia.

I became the convenor of IIgANN until I was succeeded by Renato Monteiro (Paris) in 2008, and then by Jonathan Barratt in 2016. At first IIgANN seemed to offer little other than the organisation of continuing biennial symposia. But as an era of global collaboration in IgAN research came upon us, IIgANN became an increasingly powerful facilitator of data and sample sharing (notably in pathology, genetics and the development of risk evaluation tools), as well as for trial recruitment.

Oxford Classification of IgAN

The first major international collaborative effort, which we drove from the UK, was perhaps the most challenging. In glomerular disease a number of classifications based on histopathology had emerged over the years, almost exclusively opinion-led. Renal pathologists would preconceive which features of the renal biopsy were likely to be predictive of risk, and would then group features based on their experience into a grading system (for example grades I to V in lupus nephritis). There was no such classification for IgAN so that evaluation of risk, and trial recruitment were based exclusively on clinical features.

A conversation with Terry Cook (renal pathologist, Imperial) in 2004 led us to a determination to sort this out. The Renal Pathology Society gave its support. Soon joined by Ian Roberts (renal pathologist, Oxford) we assembled a panel of renal pathologists (including most of the ‘big hitters’ on the world stage) and nephrologists and set about getting them to agree to a fresh evidence-based approach. Only pathology features whose identification was reliably reproducible would be used. In a series of meetings at Magdalen College, Oxford between 2005 and 2014 we came (after some lively and often opinionated discussion) to an objective and evidence-based classification which identified only four (later five) pathological features which were associated with outcome. This we published as the Oxford Classification of IgA Nephropathy (given the venue for its parturition), (Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society, Roberts IS et al. (The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: pathology definitions, correlations, and reproducibility. Kidney Int. 2009 Sep;76(5):546-56) which continues to be refined (Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society, Coppo R et al. The Oxford IgA nephropathy clinicopathological classification is valid for children as well as adults. Kidney Int. 2010 May;77(10):921-7; Coppo R et al. VALIGA study of the ERA-EDTA Immunonephrology Working Group; Validation of the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy in cohorts with different presentations and treatments. Kidney Int. 2014; 86:828-36; Trimarchi H et al. IgAN Classification Working Group of the International IgA Nephropathy Network and the Renal Pathology Society. Oxford Classification of IgA nephropathy 2016: an update from the IgA Nephropathy Classification Working Group. Kidney Int. 2017 ; 91:1014-1021; Haas M et al. A Multicenter Study of the Predictive Value of Crescents in IgA Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 28: 691-701) .

The early phase of work agreeing the Oxford Classification had involved sharing pathology specimens and associated clinical information from multiple centres around the world, and this built confidence and trust through IIgANN for more data and sample sharing including countries such as Japan and China where attitudes and legislation had usually limited such sharing.

A natural progression for IIgANN was then to develop a risk assessment tool for IgAN, using clinical data and pathology scoring (Barbour SJ et al. International IgA Nephropathy Network. Evaluating a New International Risk-Prediction Tool in IgA Nephropathy. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 179(7):942-952) .

Treatment of IgAN

I criticise myself because during the three decades I studied IgAN, I did not initiate any properly designed prospective treatment trials. They were few and far between throughout the time. Why was this? Choosing end points for trials in slowly progressive glomerular diseases such as IgAN remained difficult when reduction of proteinuria was not accepted as a ‘hard end point’, and trials with ESRD as the outcome were impossible – the required size and duration making them impractical and unaffordable. And there were few novel agents to study.

Even the role in IgAN of the old standby, corticosteroids, remained a matter of debate. I sparred regularly at conferences with the Italians who were convinced that they had proven the efficacy of corticosteroids, often extrapolating from small trials with slippery end points. Year in, year out when I gave a talk pointing out that lack of quality evidence meant there was still equipoise over the role of corticosteroids, Dr. Locatelli or Dr. Schena would be the first to the microphone in question time to berate me for denying my patients steroids! Their cause was not helped by their insistence that there were no adverse effects in their studies of a treatment regimen which typically included three pulses of IV methylprednisolone and oral prednisolone 0.5mg/kg alternate days for six months (…really?! ) Subsequently the TESTING trial has shown the efficacy of corticosteroids (with not insignificant toxicity) (Lv J et al. Effect of Oral Methylprednisolone on Decline in Kidney Function or Kidney Failure in Patients With IgA Nephropathy: The TESTING Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022 May 17;327:1888-1898).

Thankfully a new era was coming – a wide range of novel agents, including a number complement inhibitors were soon to be tested in IgAN, and Jonathan Barratt would be playing a leading role.

Succession planning

By 2010, I was no longer the right person to be the figurehead for Leicester’s IgAN effort. I was increasingly drawn away by my ISN work, and in any case no longer had the knowledge and intellectual agility to move the work forward into more modern approaches.

Alice Smith was still in Leicester but had given herself fully to her new interest in exercise science applied to kidney disease. Steve Harper had regrettably moved to Bristol (their gain, our loss) with an increasing reputation in microvascular biology.

Happily, Jonathan Barratt remained in Leicester and was my natural successor. He has brought in much new funding, taken the work far beyond what I could achieve, and ensured Leicester is still internationally recognised as a leader in IgAN.

Appointing successors clever than oneself is for sure the right strategy.

Author: John Feehally

Last Updated on January 12, 2026 by John Feehally