Too Hot to Handle?

Four examples and the contributors to professional dissonance.

Introduction

The ability of people to live together in harmony is something of a triumph. It is explored by modern authors as a fundamental necessity in the evolution of societies.1 The daily personal and family compromises and sacrifices we all make, to permit peaceful and productive communal relations, are enacted without self-consciousness, though with various degrees of reluctance. It is clear that consensual social conventions are essential to avoid conflict and channel any group dissatisfaction. The conventions are renewed typically in each generation. They are kept stable by the effort (energy) invested in their establishment. There is a useful analogy here with chemistry. The incorporation of ‘latent’, hidden, energy is what keeps molecules in a stable physical state, in the case of water, ice, liquid or steam. Likewise, the effortful establishment of conventions by our predecessors can be conceived as a consolidating latent energy of tradition buried in the status quo, which resists subsequent change (Brexit was the exception that proved the rule. Impatience with the deep power of tradition is being explored currently in US politics). We are also very familiar with the reinforcement of the social status quo by an exaggerated exposure of dissidents as a potentially threatening ‘other’. This high-level description is valid for whole societies and the sub-societies of which they are composed.

Despite that analysis, it has become a modern mantra that business and social success may depend on the ‘disruption’ of consensus, as a pseudo-principle advertised from vainglorious experience in business and successful technical development. Whatever the current reality, the more usual, historical, reaction to disruptive influences has been the dismissal, shunning and ultimate exile of dissidents. An analogy to the diarrheal discharge of food poisoning is obvious. In the event, societies and groups are fortunate if they can deflect or isolate the discontent of those who are unable or reluctant to conform to established routines and social interaction. Sometimes the disruptors themselves elect to leave for the less-hindered pursuit of their world view, the Pilgrim Fathers being a remote case in point. Happy the community that has somewhere to relocate its intractably discontented, an observation and benefit to which modern China seems currently blind?

Given that professional societies inevitably mirror their communal context, we can expect that UK nephrology would be able to demonstrate examples of mal-integration that have resulted in rejection and/or the voluntary migration of colleagues. Most of those are likely to be unknown because of the complexity of medical training, personal capacities and circumstances, and aspirations. Here are vignettes of a prominent twentieth century quartet that confirm the assumption. Careful examination suggests a variety of contingent causes and offers the possibility of avoiding personal discomfort and institutional loss in the future.

Some characters

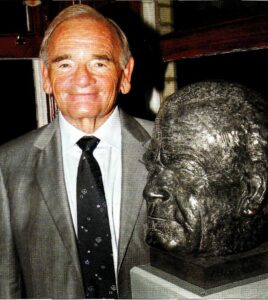

Stanley Shaldon (1931-2013)(SSh)

We have an extensive, if late in life, record of Stanley’s recollections in the ERA video library (2010) and a well-informed obituary.2,3 Stanley was comfortably cosmopolitan, coming from an immigrant Jewish family (surname ‘Schiff’- he spoke latterly, and lightly, of being a ‘wandering jew’) and early education in France. His video account is consistent with the pattern typical of post-war medical career development, including exposure to notable US personalities and research aspirations. He was independent-minded, anti-authoritarian, and disrespectful of tradition, all of which were enacted during his experiences as a conscript in the army – he extended his BTA to FTA! Professionally, he hankered for academic medical research rather than clinical immersion. He defaulted readily to idealisations of personal independence and simplicity – dialysis would be ‘the insulin of chronic kidney disease’ – consistent perhaps with a personal social release that powered his activities. He inherited the basic research emphasis of the academics of the Renal Association of the 1950s and 60s but sought a more complete reconciliation of technology and clinical applications.

His dogged enthusiasm for maintenance haemodialysis led ultimately to the establishment of a private dialysis clinic, which is seen as the UK ‘proof of principle’ for the feasibility of sustained renal replacement. Having bitten the institutional hand that fed him in London (1966), he was not appointed elsewhere in the UK. He decamped to a tolerant Montpelier (1974) for a successful European career, not least in claiming credit for resisting the exclusion of renal transplantation from the acronym EDTA! He described boredom, ultimately, with the repetitive dialysis he had fostered and perhaps he might now be described as having been partially ‘burned out’? He came to see dialysis as similar to untreatable chronic tuberculosis, tedious. A convenient formal description of him was ‘unorthodox’.

He was intimidating at the conference bar; short, and broad shouldered, with a large head and expectant, confident demeanour. He was typically brusque and cheerfully combative to all-comers, with a lifelong confrontational temperament and intolerance of timidity (vide infra).

Interestingly, one of his collaborators in London, Stanley Rosen, later the first trained nephrologist in Leeds (1966), was also very familiar with the US nephrological scene, left for California in 1974. Despite his asserted aspiration to pursue their blood flow and other research studies he defaulted to a clinical and administrative career. The disequilibrium of haemodialysis that they had explored together was mimicked in their life events!4

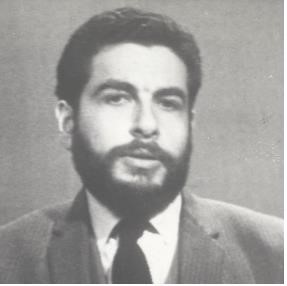

Geoffrey Merton Berlyne (1931-2007)(GMB)5

This Manchester-trained nephrologist was ultimately an academic émigré to Israel and then the USA. He was academically outstanding and recognised as unusually talented by colleagues. He supervised early haemodialysis at the Manchester Royal Infirmary (MRI) but was appalled by the hepatitis outbreak of 1966, which infected both him and his trainee, Peter Ackrill. He was intemperate about the origins of the infection, a tendency that was witnessed also in personal relations, and repeated in his inaccurate and controversial 1982 editorial in the Nephron, the international renal journal he edited for years (in the struggling UK dialysis programme that he pilloried, he was adrift by a whole decade of the de facto limit of treated patient age (60 not 50 years)).21 He emigrated to Israel after closure of the MRI dialysis unit in 1968. He was recognised as clinician and productive researcher, later holding a chair in New York from 1976-1996. He had a deep interest in nutrition, dietary management of renal failure and body composition, including aluminium.6

He also described in 1967 one of the diagnostic treats of clinical examination.7 The dramatic red ellipse of alkaline crystal conjunctivitis, revealed against a white sclera by merely lifting the eyelid of those with the raised CaxPi products of renal failure, never fails to gratify. That colourful outward sign of inward biochemical disturbance is yet more graphic than, say, the reduced overnight Se Pi (reduced TmP/GFR) pointing to hyperparathyroidism (with preserved renal function).8 As a practising Jew, he qualified as a rabbi aged 70 and became fluent in Arabic.

In the UK, his brother practiced as a much-appreciated psychiatrist in Oldham, dying at 93 in 2021.

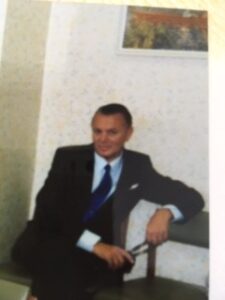

Martin Knapp (1935-)(MSK)

One of the lively consultant agents of the 1966 DoH commitment to regional maintenance dialysis centres, Martin set up the renal unit in Nottingham. He gave his spare energies to establishing local renal transplantation and was very active in the national effort to increase NHS funding for renal replacement across the 1970s.9,10 He was the first adopter of clinical computing from the CCL system that came out of the insights of Hugh de Wardener at Charing Cross. He also pursued time series measurements of rejection in renal transplantation that were a basis for the notable career of Professor Sir Adrian Smith in statistics and probability theory.11,12 Martin carried a life-long preoccupation with chronobiology and its advocacy. He set up and staffed a local laboratory to study it, only to be refused scope in NHS employment to develop the work further.13,14 That resulted in his resignation from the NHS in 1983. He worked subsequently in Saudi Arabia and Australia, as a physician in Tasmania and subsequently a sometime flying doctor, retiring to Melbourne. He remains deeply interested, and published from retirement, in chronobiology.

E Nigel Wardle (1934-2020)(ENW)

A trained physician, Nigel was something of a biochemical nerd, obsessed with the intricacies of biomolecules that might explain the pathophysiological phenomena of disease. He was shy and serious-minded. He was explosively productive in animal and laboratory research from posts in Newcastle, King’s College and Saudi Arabia from 1968 to 1987. There were few clinical topics that he did not address. His modus operandi was often through journal letters, responding to articles, pointing out additional evidence and then posing the implications for further research. Of course, speculating about molecular mechanisms has generally been more indulged in the profession and medical publishing than clinical flights of fancy. He took that opportunity to the extreme. A paper in the journal ‘Medical Hypotheses’ was quite characteristic. He wrote four textbooks, between 1979 and 2012.15-18 He did not find a comfortable academic home in the UK, working latterly in locums, publishing from a private, personal base for many years. It seems that he was offered FRCPE not FRCP Lond.

Comment

These four individuals were highly talented and energetic. They did not fulfil their academic or clinical potential, and were lost to nephrological training, in the UK. The first three had experienced US healthcare and productive research first-hand, SSh with Kolff and MSK with Bricker and Avioli. That may have left them with a residual confidence in free-thinking and an extended research horizon. They were all focussed on academic abstractions, which they pursued intolerant of boredom, and were self-motivated. Intemperance and/or relative impatience with less academically committed colleagues characterised the first two. They lived in an intellectual climate that was universal, which, together with a certain incidental cosmopolitanism and family background, meant that they were able to indulge some of their preoccupations ultimately outside the UK. MSK could not recover the facilities he had developed in the UK. The emigrations must have involved a range of personal sacrifices, as well as any gratifications.

They interacted, as it happened; the first two indirectly regarding salt and pre-boiled potatoes in renal diets (!) and ENW responded to the 1982 Nephron critique of the adequacy of UK renal replacement.19-22

Characteristics and consequences

Incompatibilities

They were rejected essentially by the specialty in the UK, through an inability to find permanent, congenial employment. Their reciprocated rejections of the opportunities offered by the UK specialty were manifest. As discussed elsewhere, the job mobility which has been a feature of developing a specialty career in the USA has not been common in the UK, and even disparaged.23

An incompatibility with English attitudes and arrangements for research may have been only one explanation of events, since inter-personal dissonances seem likely to have contributed. The style and expectations of English nephrologists were set by national professional attitudes in medicine and, perhaps, by the academic origins of the Renal Association. With a tendency to romanticise that origin, the preference for aping 19th century dilettantism in science and an Apollonian modesty were the preferred personal style, as demonstrated nationally both in job appointments and historical biographies. There was a certain consensual politesse. Notwithstanding, a male playfulness characterised specialty meetings, and some colleagues even ventured ‘laddishness’ after the millennium. Serious-mindedness was tolerated typically only by expressing a pointed irony or attempts at personal deflation. A neglect, or effectively a challenge, to specialty social conventions generated strong interpersonal reactions.

Conversational style

Given that context it is perhaps unsurprising that a challenging style of conversation was not appreciated in contact with the first two (SSh,GMB) of our quartet. There is a clue in their personal origins. Others have commented on the Jewish tradition of a search for truth through argument, with examination of all aspects of a proposition through questioning, objections and vigorous exchange.24 It is apparent that if conversational assertions were taken as implicit or rhetorical questions, an instinctive launching into objections and vigorous debate would come as a shock to non-Jewish interlocutors. The suggestion is of an inadvertent collision of conversational styles in specialty encounters, added to whatever personal eccentricities the parties already unselfconsciously enacted.

Seriousness

The other stylistic contrast may have been the commitment to a sober seriousness in addressing a topic. In conversation or presentation that approach sat uncomfortably with the typical English presentation, which valued a self-deprecating and even comedic turn. The popular drolleries of the RCP’s David Pyke were archetypal. Certainly, a group guffaw of whatever origin halted any further discussion, readily ‘bringing the house down’.

As indicated, all four were preoccupied with abstractions that drove their uncompromising intellectual attitudes. In the case of ENW there was something of an indifference in meetings to his encyclopaedic contributions, being presented to a less driven forum. His publications and books were then a remarkable testimony to persistence in the face of specialty neglect in public.

Possible consequences

It is not far from such contrasts of style to an exaggeration of difference that becomes used unconsciously to label ‘the other’ and very usefully consolidate group identity. Polishing the group image is a good preparation for taking pride in it and rewards individual participation.

A lack of generosity and sluggish acceptance has been an occasional feature of RA behaviour, relating to the very early haemodialysis special interest group and, arguably, clinical IT after 1981. There have been, and are still, others in the specialty a whisker away from the experiences described here, who have made their peace with specialty conventions or who have been fortunate in the opportunities they were offered. Others, unidentified, will have decamped.

The cost of cultural prejudices

In a western social culture that publicly idolises obsessional commitment and disruption of the status quo it is pertinent to be aware of the paradoxical risk of intellectual obsessions when they cannot find a fit to the contemporary consensus. There is a personal and communal cost to expressing minority dissonance, similar perhaps to the accepted price of RTAs consequent on road transport, and pusillanimous firearm control that permits repeated school massacres and a high completed suicide rate in the USA? The executive of the RA seems not to have actively mitigated individual dissent and/or eccentricities. Until the 1990s the self-image of the RA was of a scientific body, with no formal political or employment role. No one body was responsible for the twentieth century professional and NHS binary, but these were ultimately losses to UK nephrology.

Task and temperament

It is apparent that the personal qualities required to forge a new entity, or academic understanding, are rather different from those best able to subsequently develop and sustain it. Setting up renal replacement capacity, whether largely technical or organisational, demanded an uncompromising mindset that might not adjust to routine, and which had a good chance of becoming a nuisance once originality, flexibility and creative ideas were no longer required. The troubled, post-millennial, staffing of the UK Renal Registry suggests as much. The history of the NHS suggests that once the pattern of clinical services was well-enough discerned, across the end of the millennium, further (expensive) development was largely eschewed, and such transitions avoided. There are then inevitable casualties in the progression from the novel to the routine. A greater awareness of that hazard might mitigate the risk of personal disadvantage and organisational impoverishment, the need for which is well demonstrated by these four examples.

The individuals presented here chose, under some duress, a productive exile or an element of professional isolation. The cost of sustaining comfortable group conventions and coherence in the specialty was manifest and salutary. Sometimes a stretching of conventions is irresistible in the course of self-definition and pre-occupation, in which case one may become, for the specialty group, too hot to wish to handle.

References

- Harari YN. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Vintage. 2015.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QzIrg4AgXcE

- https://www.ukkidney.org/about-us/history/obituaries/stanley-shaldon

- Rosen SM, O’Connor K, Shaldon S. Haemodialysis disequilibrium. 1964 Br Med J; ii (6410) :672-5. doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.5410.672

- Geoffrey Merton Berlyne 1931-2007. Nephron Clin Pract 2008;109:cI. doi:10.1159/00013563

- Berlyne GM, Yagil R, Ben Ari J, Weinberger G, Knopf E, Danovitch GM. Aluminium toxicity in rats. Lancet 1972;1:564-567

- Berlyne GM, Shaw A. Red eyes in renal failure. Lancet 1967; 1(7480):4-7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(67)92418-x.

- Bijvoet OL. Relation of plasma phosphate concentration to renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate. Clin Sci 1969;37(1):23-36.

- https://ukkidneyhistory.org/timeline/1980s-scaling-provision/tactics-and-strategy-local-and-national-initiatives-in-uk-nephrology-prior-to-1990/

- Knapp MS.Staffing problems in nephrology. Br Med J 1976;2(6045):1198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6045.1198-a

- Trimble IM, West M,Knapp MS, Pownall R, Smith AF.Detection of renal allograft rejection by computer. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;286(6379):1695-9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6379.1695.

- Knapp MS, Smith AF, Trimble IM, Pownall R, Gordon K. Mathematical and statistical aids to evaluate data from renal patients. Kidney Int. 1983;24(4):474-86. doi: 10.1038/ki.1983.184.

- Knapp MS, Keane PM, Wright JG. Circadian rhythm of plasma 11-hydroxycorticosteroids in depressive illness, congestive heart failure, and Cushing’s syndrome. Br Med J 1967;2(5543):27-30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5543.27.

- Knapp MS.Nocturia and Reversed Circadian Rhythms. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1969;3(4):398-405.

- Wardle EN. Guidelines in Medicine. Renal Medicine 2. MTP Press, Lancaster 1979.

- Wardle EN. Cell surface science in Medicine and Pathology. Elsevier Science Publishing Company

- Wardle EN. Glomerulopathies. Cell Biology and Immunology. harwood academic publishers. CRC Press 1996.

- Wardle EN. Guide to signal pathways in immune cells. Humana Press, USA. 2009.

- Berlyne GM, Janabi KM, Shaw AB. Dietary treatment of chronic renal failure. Proc Roy Soc Med 1966;59:665-7.

- Kerr DNS, Robson A, Elliott W, Ashcroft R. Diet in chronic renal failure. Proc Roy Soc Med 1967;60(2):115-6.

- Berlyne GM. Over 50 and Uremic. Nephron 1982;31:189-190.

- Wardle EN. Over 50 and Uremic. Nephron1983;33(3): 224. doi:10.1159/000182947

- https://ukkidneyhistory.org/units/renal-units-pride-in-and-of-place/

Authorship

First published 24 April 2025

Last Updated on July 16, 2025 by John Feehally