On Salience

by Es Will

‘Until recently (2023), the focus of nephrology care for dialysis patients has been related primarily to numerical targets for laboratory measures, and outcomes such as cardiovascular disease and mortality. Routine symptom assessment is not universal or standardized in dialysis care.’1

Contents

Introduction

A medical specialty like Nephrology is partly characterised by its preoccupation with a range of clinical and research topics. They form a backdrop to everyday activities and aspirations as an invisible ethos, both local and universal. Properties like the potential for technological improvement and the mitigation of intractable problems in treatment typically dominate the practical agenda. By contrast, core features of patient care that might prompt research and development interest are not always prominent and their recognition would vie with many other demands.1-3 That pitfall was described, if not fully recognised, very early in the developing specialty.4-6 Was there a historical trajectory to the emphasis on treatment at the expense of patient care?

Pictures and Words

The attraction of topics to the medical mindset is complex. In Nephrology, the glomerulus has a long history of seduction to a commitment of time and effort, drawn from a sustained visual affect.7 It is apparent that mankind is highly ocularcentric, vision being the main means of acquiring everyday situational awareness from what we might call spectatorship. That sensory domination has philosophical and historical importance.8,9 It determines the attention given to visual stimuli, just as dogs, say, are irresistibly drawn to odours. The stimulus offers an immediate affect and then content, with intriguing potential. It reinforces modern internet scrolling and the Media obsession with images accompanying on-line text, for example.

More specifically, the unavoidable appearances of human anatomy were an obvious prompt to a focus on organ systems in Medicine, embellished subsequently by the unveiling of patho-physiologies; form was followed by function. That medical phylogeny has been the platform and credential of the traditional ontogeny of medical education. The challenge of understanding pathological states encouraged the discriminating and optimising mindset of the clinician, diagnosis being the key to the social and personal rewards of medical practice. The more abstract properties of patient care were harder to express and celebrate except figuratively, often delegated to nurses seen to occupy a nurturing biological and social role. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the more tangible, focal, treatment elements seem always to assume more salience than the universal abstractions of patient care.

The origins of specialty salience – two evolutionary narratives

The salience of a topic in a medical specialty develops from a variety of prompts, some clinically inevitable, others only predictable with hindsight. For example, the acceptance of older patients for dialysis after 1980, and the ageing of treated dialysis cohorts, ultimately provoked concern for their appropriate management by physicians trained in General Medicine. It was fully exposed by the uncomfortable supervision of elderly patients made even more symptomatic by the variable success of the vascular access procedures seen necessary to prolong lives of limited ‘quality’. The conflict of Cure and Care became stark, in that setting of surgical impracticality and resource constraints. Subsequent studies of survival and suffering revealed an age, gender and resource related matrix of benefit and disbenefit from non-dialytic conservative management (CKM).10-12 That has become a consensus practice, albeit variably discharged at local level.13-15 Despite the longstanding recognition of Care of the Elderly as a specialty by the medical establishment there seems to have been little early co-ordination with that expertise at renal unit level.16

The CKM approach was initially designated as palliative, although of course all renal replacement can be considered as such. The late formal recognition of Palliative Medicine (PM) by the Medical Colleges in 1987 depended partly on recognition of the need for expert clinical management of opiates for pain relief and comfort at the end of life.17 Years later, hospice-trained clinicians were invited to lecture on safe opiate use in renal failure at UK Nephrology meetings. They came to realise that their acquired skills in symptom control could also be usefully advertised in renal medicine. Their talks became structured, to first rehearse their credentials covering opiate caveats, followed by a discussion of methodologies of symptom relief. The presentation of their experience turned out to be important as an expert professional entrée and prompt to the long-neglected dimension of symptom control in the specialty (see postscript).1

The further origins of specialty salience

Other promotions of salience have depended on entrepreneurial colleagues, who discover neglected areas of professional activity in the course of their career development. Any subsequent penetration in the specialty has depended on the prevailing scientific and clinical consensus, as well as the contribution to understanding. Developments outside the specialty also provoke salience, since medical researchers are drawn to the digitally well-characterised predicament of readily accessible (renal) patients. The University of York QALY proposals of the mid 1990s were a case in point, although there was little specialty response to grass-roots Quality of Life initiatives at the time of their ultimately published academic survey of QALYs in renal medicine.2,18

It would be incomplete not to mention that some topics develop and recur regardless of specific professional prompts. Racial issues, for example, resurface periodically, perhaps because the visual signal of race is so much stronger and uniform than its cultural implications.

Focal Points

It is apparent that there is an imbalance in the manifestations of medical science and medical humanities, in terms of their advertisement and expressible benefits. As a special case, Epidemiology is accepted as ‘scientific’, being numerate through statistics, counting and calculation. It mediates the treatment/care clinical divide? Issues that are not readily quantified cannot exist in Science, according to some, which can be taken too literally in denying claims of salience.19 The imbalance is undesirable at the level of patient practice and arguably requires deliberate promotion through semantics to restore clinical emphases. How far terms reflect the changes in perceived salience, rather than just promote a recognition, remains to be seen.

It is impossible to ignore the importance of terminology in the history of salient clinical topics. Just as the glomerulus seems to call out to some, so particular terms usefully stimulate and focus attention on neglected clinical issues. In patient care, the shift of vocabulary towards Frailty, symptom Burden, (uraemic) Itch (compared to vomiting, say) and Depression represents more coherent, apparently stimulating, clinical topics, than the broader clinical categories of Ageing and the Psychosocial.20,21 The preference for a prefix of ‘Living with …’ emphasises the patient care dimension and softens the terminology. Of course, the extent to which a topic offers a perceived opportunity of solution and clinical progress must also be relevant in attracting the commitment of time and effort of researchers. Clinical terms, like Frailty, have also been seen to unlock material resources to pay for clinical management, once a special need was recognised.

The evolution of renal initiatives is not always consistent with expert opinion. The aggregating syndrome of Frailty was not necessarily the useful trigger in Geriatrics that might have been supposed. A greater understanding in that specialty was being sought through unpacking the treatable components of ‘Living with Frailty’.

The disturbance of mental health provoked by renal replacement has long been designated ‘Psychosocial’ as a compliment to the inevitable social dislocations created by treatment. It is a more euphonious term, perhaps, than the more directional ‘socio-psychological’. ‘Psycho’ as a suffix proved to be useful elsewhere, since ‘Psychonephrology’ was a productive occupation for several research groups abroad in the mid-1970s and subsequently.22-23 The literature was sustained by a few individuals, for example the contributions of Norman Levy, AK De-Nour (from 1968-1996) and latterly Paul Kimmel. However, an effort to understand the consequences of a pot-pourri of psychological, social and frank psychiatric presentations in renal failure can be profligate and self-defeating. A focus on a characterisable (through survey) disorder, like Depression, facilitates clinical research, much as it incentivises Big Pharma drug development and marketing.24,25 Whatever the vocabulary, the routine availability of psychiatric support for UK medical wards was late in coming and patchy when it did.26,27

Sometimes a clinical feature that seems useful in calibrating risk is promoted as a noun entity even before its criteria are fully consolidated, as with Cachexia.

The neglect of symptom control in renal replacement, in particular, was remarkable (see anecdotal postscript), especially since the newer specialty of Medical Oncology was developed from an early awareness of that very need in the mid-1980s.28

Marketing through terminology

The universal use of acronyms in multicentre research studies has shown the benefit of labelling projects, because such fictions objectify effort and aspiration by acting as ‘brands’. A study brand name is particularly helpful when many centres are involved. Acronyms identify entities that can be characterised through the development of study protocols and subsequently used to first trail and then publish results. For best they are not just codes but more like Quick Crossword clues.

It is helpful if studies can be presented with some element of glitz or allude to universal, creditable entities (PIVOTAL, AMPLITUDE, APOLLO).29 Apart from anything else, attracting funds for research is a marketing exercise, as is the ultimate advertisement of results. Of course, the sparkle can be a glister that is not gold! The current, essential, studies to validate new pharmacological agents for renal disease prevention must be harder to colour with any kind of charisma than the meaty, discrete, scientific topics of the past. There is always a possible default to word salads (e.g., PARASOL).

The utility of PROMs and PREMs, in proportion to the effort of their collection, seems yet uncertain.30 Unfortunately, repeated personal enquiries can quickly become tedious and the responses unreliable, according to experience with haemodialysis symptom reporting. The ideal of patient consultation can also founder in the face of advertised incentives to respond that are widely known to be undeliverable. IT potential is prone to create data before its most useful application is discovered.

Terminological overreach

Terminology, then, can present a class of social conventions, to facilitate exchange of ideas and focus collaborative effort. Labelling allows a consolidation of interest for professionals and serves as a rallying point of joint enthusiasm. The expression ‘salient’ itself implies phasic attempts at understanding, within a culture of professional common knowledge and coordination, as explored by Stephen Pinker.31 Did the useful exercise of naming issues have historical consequences for specialty attention?

In the mid-1980s, in an effort to increase NHS resources for the ever-increasing demand for renal replacement, the Renal Association was drawn into giving titles to novel committees that were tasked with surveys of Manpower and Workload. Well-intentioned sub-groups were later nominated and charged with the development of Trials, Education, Audit, Standards and the Renal Registry. The energy diverted into these designated initiatives did not seem to leave much for the topics of clinical care, as less coherent abstractions. Diabetes had its influential advocates, which made it exceptional.2 Ageing, Mental Health, Palliative Care, Quality of Life and Symptom Control were not privileged initially by separate terminologies, nor were they much in evidence in medical meetings or research.2,3 Nephrologists were formally encouraged to instigate clinical specialty liaisons only well after the millennium.32

Opportunity Costs

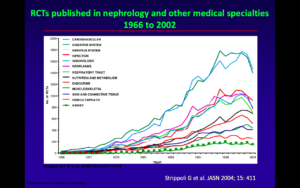

Indeed, in the pre-millennial decades there appears to have been a relative void or pause in the focus on patient care at a strategic, specialty level. This can be seen as a consequence of the dominant effort to quantify demand for treatment and press for extra resources. Such opportunity costs are only too easy to neglect, especially when the bread-and-butter pursuit of the ideals of renal research in bi-annual ‘scientific meetings’ had also to be sustained. Concern for the momentum of the very strong academic traditions of Nephrology arguably absorbed some of the available medical attention, evidenced by a revealing survey of renal research in academe (1989-93).2 A specialty deficit in RCTs was well recognised.33

Confounding factors

Several clinical and circumstantial factors are likely to have played a part in a flat trajectory of renal patient care research and practice. Only after 1980 were older patients offered for renal replacement, ultimately including those with diabetes. Expertise in the care of the aged and diabetic became much more relevant thereafter.

The involvement of Primary Care was minimal in the early decades of dialysis, but gradually impinged and diluted the necessity for, and comprehensiveness of, nephrological supervision in secondary care. The idiosyncrasies of UK renal centres have long been recognised.34

Whilst the research contribution of BRS often addressed treatment issues, it is apparent that patient care initiatives were not uncommon. However, they were typically unit centred and did not generate system-wide studies and practices. The Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) ethos motivated and structured non-medical activity, but in the absence of a Renal-National Service Framework (R-NSF ) model any integration of regional and national efforts was leaderless.

A refinement of the areas of interest was also apparent in the focus on rare diseases (RADAR) and other surveys. They provided an important focus for enthusiasts, encouraging personal investment in studies and more scrupulous data collection, for example.

Funding for research was for many years a local affair, subject to unit-related aspirations and interests but typically free of peer review, independent monitoring and sanction. Multicentre studies and RCTs were noticeably less frequent in Nephrology than other medical specialties. The 2006 advent of the National Institute of Healthcare Research (NIHR) brought a range of critical mechanisms to bear, allowed diversification of topics towards patient care and facilitated multicentre studies.35

Further archival work in this complex professional melee is required, to consolidate the interpretation of a significant opportunity cost consequent on political and organisational usurpations of salience in the specialty. The potential influence of the parallel factors above could also be characterised and assessed for relevance.

After the pause

The care elements were addressed in detail by Nephrologists well after the personnel and resource requirements of palliating renal failure became accepted within government and the NHS around 1990. Clinical features were revisited initially through the R-NSF of 2007-8 and the progressive empowerment of non-medical staff after the millennium, based especially on CQI. A vocabulary of topics more evocative of patient care was fashioned subsequently (see above). Large scale, carefully designed, well resourced (NIHR), multicentre studies have become more accepted into the salient topics of UK clinical care in the second decade after the millennium.

Conclusion

Over time, there have been shifts in the topics believed to be important in Nephrology, as in any medical specialty. Salient topics promote attention, understanding and/or solution. Their terminology is culturally influential as a prompt and reinforcement of specialty awareness and activity. The wrangling of the Renal Association with the UK government in the 1970s and 80s for resources to address a burgeoning demand for renal replacement seems to have diverted attention and research from patient care. The traditional momentum of investigatory renal science and academic topics by the Renal Association was sustained. That neglect was subsequently part-corrected in the attempts at a blue-print for nephrological practice in the unimplemented R-NSF. The rebalancing of treatment and care was pursued more successfully in the second decade after the millennium, with the salience of patient care flagged by a more focused clinical vocabulary. The prompts and means to that re-alignment deserve further historical examination.

Acknowledgement: with thanks for the comments of Prof Ken Farrington, University of Hertfordshire and Lister Hospital, Stevenage.

Historical Post-script

The concern to fill the relative voids in patient care leaked periodically into pre-millennial professional agendas.2,3 The UK introduction of renal clinical computing after 1979 can be seen as another diversion from a clinical preoccupation with patient care, a seductive technological abstraction that offered a quantitative situational awareness to specialty tasks. However, there were possibilities for that new dimension to improve patient care.

One of those was revealed on my personal visit to the Detroit renal unit of Nathan Levin in the early 1980s (he is active in hollow fibre water supply purification, at the age of 91, in 2026). The mini-computerised Detroit centre registered haemodialysis symptoms digitally to a data vault, but in such detail that they were not readily aggregated or perused. Returning to the UK, I used the CCL (Clinical Computing Ltd) mini-computer system at St James’s University Hospital, Leeds to register dialysis symptoms in a more restricted, cumulative format of five categories (to include then severity and frequency), as the basis of a randomised study of symptom relief by Gambro Haemofiltration Vs. standard Haemodialysis. I presented the potential study protocol to a Renal Association meeting in May 1984 in a stepped, classical Boerhaave-style lecture theatre.36 A very well-established clinician in the front row, legs akimbo, commented at the end “so you can measure dialysis symptoms, so what?” The audience collapsed, guffawing noisily in that confined space, and any response was impossible. As a recently appointed consultant I was entirely disarmed.

Comment

The comparative dialysis study was never attempted for other reasons. However, a digital dialysis symptom record on all haemodialysis patients was kept routinely for many years at St James’s, with later improvement.37 The symptom record was used to ameliorate the periodic haemodialysis intolerance of centre and satellite patients.38

It is impossible to know whether a more insightful response at the meeting would have promoted development focused on symptoms, but that was more than forty years ago and twenty years before symptom control acquired any national and international salience. Perhaps presentations are worth a deliberate, periodic review, to detect where the ethos of the specialty leviathan seems to be going or could go; a routine inspection for overlooked strategic salience?

References

- Mehrotra R, Davison SN, Farrington K et al. Managing the symptom burden associated with maintenance dialysis: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2023;104(3):441-454. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2023.05.019.

- Renal Association Executive Committee minutes 1976-2000. Wellcome Collection Library Archive, London.

- Renal Association AGM minutes and scientific programmes 1982-1992 and 2000-2002.

Wellcome Collection Library Archive, London.

- Merrill JP. The treatment of renal failure. 1955. Grune & Stratton. New York and London. p163.

- Cameron JS. Words. Guy’s Hospital Gazette.1967;81(3):129-131.(text available from this author).

- Living with Renal Failure. Eds Anderton JL, Parsons FM, Jones DE. 1978 MTP Lancaster.

‘What are the inner thoughts of patients who spend many hours strapped to a machine? Is it a bearable life?’

- Will E. https://ukkidneyhistory.org/misc/the-glamour-of-the-glomerulus/

- Kavanagh D. Ocularcentrism and its Others: a framework for metatheoretical

Organization Studies 2004; 25 (3): 445-464. doi. 10.1177/0170840604040672.

- Guthrie D. Whither Medical History? 1957 Royal Society of Medicine. Published online by Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/S0025727300021487.

- Chandna SM, Schulz J, Lawrence C, Greenwood RN,Farrington K. Is there a rationale for rationing chronic dialysis? A hospital based cohort study of factors affecting survival and morbidity. Br Med J 1999;318(7178):217-23. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7178.217.

- Smith C, Da Silva-Gane M, Chandna S et al. Choosing not to dialyse: evaluation of planned non-dialytic management in a cohort of patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephron Clin Pract. 2003;95(2):c40-6. doi: 10.1159/000073708.

- Walker H, Carrero J-J, Sullivan MK et al. The kidney failure risk equation in people with CKD and multimorbidity: the effect of competing mortality risk. Nephrol Dial Transplant2025;, doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaf252.

- Roderick P, Rayner H, Tonkin-Crine S et al A national study of practice patterns in UK renal units in the use of dialysis and conservative kidney management to treat people aged 75 years and over with chronic kidney failure. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2015.

- Wennberg JE. Effective Care: A Dartmouth Atlas Project Topic Brief. Lebanon (NH): The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice; 2007.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK586630/

- Appleby J, Raleigh V, Frosini F et al. Variations in health care. The good, the bad and the inexplicable. The King’s Fund. 2011. ISBN: 978 1 85717 614 8.

- Brown EA , Farrington Geriatric Assessment in Advanced Kidney Disease. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(1):27-39. doi: 10.1177/1049732314549030.

- Overy C, Tansey EM. (eds) (2013) Palliative Medicine in the UK c.1970–2010. Wellcome Witnesses to twentieth century Medicine, vol. 45. london: Queen Mary, University of London.

- Gudex CM. Health-related quality of life in endstage renal failure. Qual Life Res 1995;4:359–366.

- “ I often say that when you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it; but when you cannot measure it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meagre and unsatisfactory kind; it may be the beginning of knowledge, but you have scarcely, in your thoughts, advanced to the stage ofscience, whatever the matter may be.” Lord Kelvin 1883. Lecture on Electrical Units of Measurement (3 May 1883), published in Popular Lectures vol1, pp83.

- Rayner HC, Larkina M, Wang M. et al. International Comparisons of Prevalence, Awareness, and Treatment of Pruritus in People on Hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(12):2000-2007. doi:2215/CJN.03280317.

- Rayner H, Sukul N. Fast Facts: Kidney Itch: CKD-associated Pruritus: Under-recognized and Under-treated. 2022. Karger SG. 72 pages.

- Levy NB. Bull Menninger Clin. Psychological complications of dialysis. Psychonephrology to the rescue. 1984;48(3):237-50.

- Levy NB. What is psychonephrology? J Nephrol. 2008 Mar-Apr;21 Suppl 13:S51-3.

- Pearce CJ, Hall N, Hudson JL et al. Approaches to the identification and management of depression in people living with chronic kidney disease: A scoping review of 860 papers. J Renal Care 2023;50(1):4-1 doi:10.1111/jorc.12458. (Papers after 2009 only).

- Gregg LP, Goodman L, Carroll EQ, Hedayati S. A practical primer on how to detect and treat depression in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2025. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2025.07.020.

- House,A,Hodgson, 1994. Estimating needs and meeting demands.

In Liaison Psychiatry: Defining Needs and Planning Services (eds Benjamin, S., House, A. & Jenkins, P.). London: Gaskell.

- Walker A, Barrett JR, Lee W et al. Organisation and delivery of liaison psychiatry services in general hospitals in England: results of a national survey. Br Med J Open. 2018;8(8):e023091.doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023091.

- Selby P, Chapman JW, Etazadi Amoli J et al. The development of a method for assessing the quality of life of cancer patients. Br J Cancer 1984;50:13-22.

- Will E. https://ukkidneyhistory.org/misc/too-nice-to-resist-the-use-and-abuse-of-pleasantries/.

- Sharma S, Beadle E, Caton E et al. The Role of Patient-Reported Experience and Outcome Measures in Kidney Health Equity-Oriented Quality Improvement.

Semin Nephrol. 2024;44(3-4):151553. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2024.151553.

- Pinker S. When everyone knows that everyone knows. 2025. Allen Lane (Penguin Books). ISBN 978-0-241-61882-0doi/

- Royal College of Physicians. The changing face of renal medicine in the UK: the future of the specialty. Report of a Working Party. London: RCP, 2007.

https://rpsg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/The-Changing-Face-of-Renal-Medicine.pdf.

- El Kossi M, Khwaja A, Meguid El Informing Clinical Practice in Nephrology. The Role of RCTs. 2015. Springer International, Switzerland. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-10292-4.

- Will E. https://ukkidneyhistory.org/misc/shaping-the-uk-renal-unit-archipelago/

- https://www.rand.org/randeurope/research/projects/2016/nihr-ten-years.html

- Will EJ, Read DJ, Davison AM, Lewins AM. Continuous measurement and display of the symptom ‘cost’ of Haemodialysis. Renal Association Abstract. 1984.

https://abstracts.ukkidney.org/wp-content/documents/1984-1988021.pdf

- Kanaa M, Lindley EJ, Bartlett C, Will EJ, Wright M. Assessing and recording dialysis tolerance. Br J Renal Med. 2007; 12(3):30-33.

- Will E. https://ukkidneyhistory.org/units/leeds/more-on-st-jamess-university-hospital-renal-unit-1980-2007/

Last Updated on February 2, 2026 by John Feehally