Renal PatientView

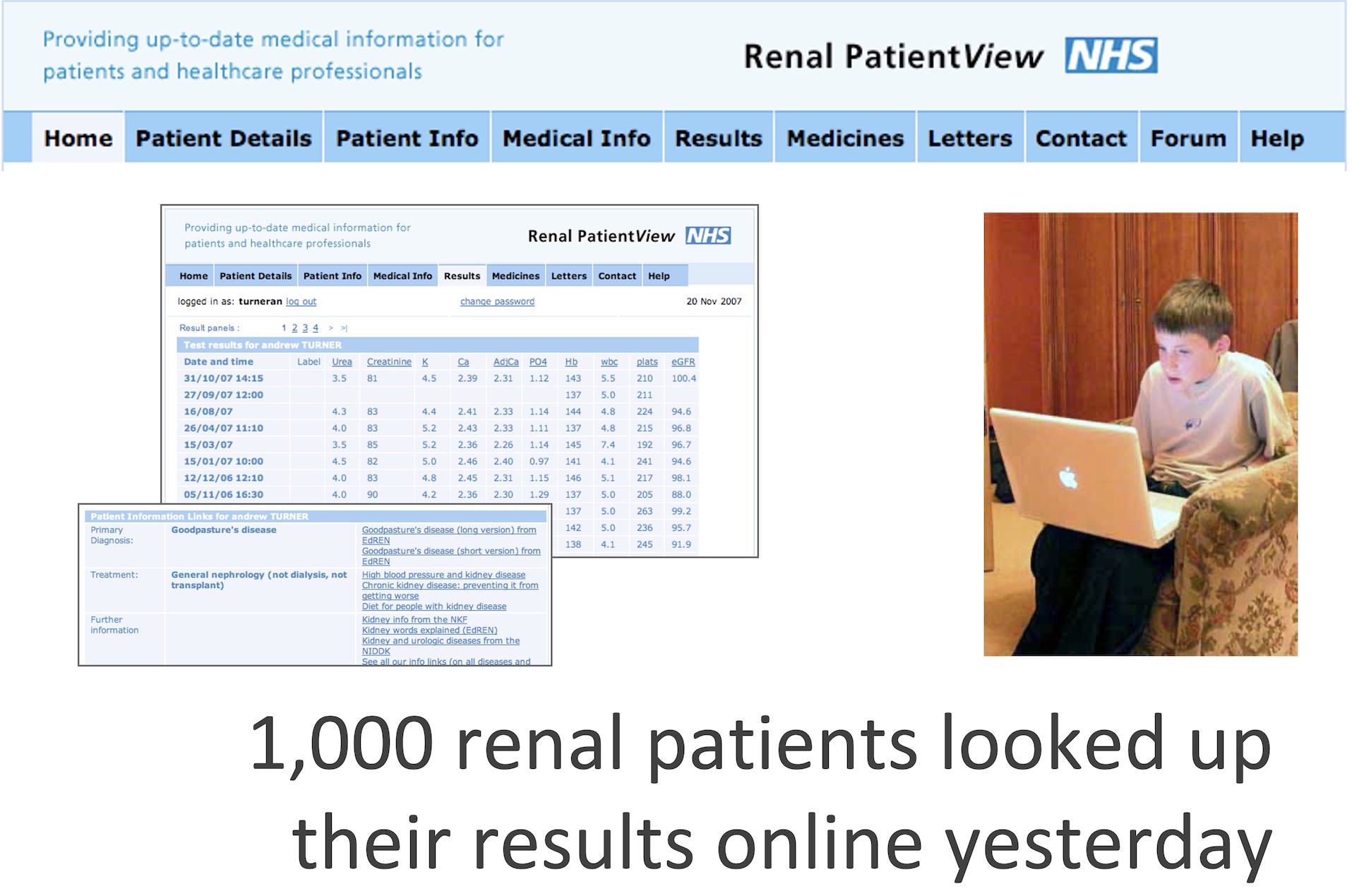

Image: screens from an early version of Renal PatientView, November 2007.

In 2005, RPV was a first in UK health care, a digital system allowing patients and carers to have password-protected access to their clinical information held in their local renal unit IT system through an intermediate web server.

Thanks to pioneering work in the 1980s, renal units had advanced internal electronic records systems compared to most other specialties (see Renal IT, and Proton). From 2000, private companies began to approach professional associations, offering to create websites, databases, or other electronic services. It was decided to review what developments would be most desirable for the wider renal community.

In 2004 a gathering of UK patients and professional organisations met as the Renal Information Exchange Group (RIXG), convened by John Feehally. A major focus from the beginning was how to exploit advances in IT to improve patient experience, which had been barely changed by them so far. After demonstration of the electronic resources available to clinicians, the top priority of patient representatives became to see their own results. This was supported by the clinical professionals on RIXG, leading to testing of how this could be achieved, and what the reception might be.

Contents

Piloting

An early decision was to use the Internet rather than discs, CDs, USB drives, or terminals in hospitals, as had been used in some experiments elsewhere. A small scale local pilot of the feasibility of exporting results to a website was successful, and RIXG patients and professional members were enthusiastic.

John Feehally led a bid from RIXG that obtained a £75,000 grant from the Department of Health to establish proof of principle. A small steering group led by Neil Turner (Edinburgh) and Keith Simpson (Glasgow), collaborating with an independent web developmer Rob Worth, and a project coordinator Andrew Scott, had established a working pilot scheme in four renal units which used Proton by 2005. Among the issues addressed in this pilot were

- Making operation sustainable. No extra clinician time was expected to run it, and minimal additional staff time overall. Local management of new logins and questions about ‘where is my creatinine from Tuesday?’ were managed by a local IT or clerical administrator, usually existing posts.

- Permission to export data. There was no established route to gain permission for patients to be shown their own results online at this time, only a very slow process to request access to paper records. Efforts were made to find authoratitive opinions from senior NHS sources to help local Caldicott Guardians to understand and approve the intentions, process, security, and support available.

- What was sent – initially just results, but extending in the pilot to showing the specific renal diagnosis recorded (as a code) in the electronic record, and a free text view of a current problem list, and of drugs recorded in the renal unit.

- How to export it – consistent formats for transfer of clinical data between different systems were not in place. A ‘PatientView XML’ format was created for exporting data from any clinical record system to the PatientView server. This remains in place more than 20 years on.

- Information to support interpretation of test results was written, but information about the different renal diagnoses was linked from other reliable sources (sometimes leading to them adapted by the providers). Links to these sources could be edited by system administrators on the PatientView server.

- Live or delayed results? There was some anxiety at the possibility that shocking or dangerous results (e.g. very high potassium values; and later on, changes in viral serology or PCR results) might be seen by patients first, rather than delivered by a clinician. On the other hand, pre-approval of results would require extra clinician time, and delay the results getting back to patients. It was decided to pilot live, immediate release (for most data, the same day or the next morning).

- Direct importing of Transplant status from the national transplant database in Bristol was implemented early, as there had been several cases where patients believed that they were active on the Transplant waiting list, but it turned out that this change had not been made on the national database. Weekly automated queries about status of patients on RPV were sent to the Bristol database and status returned.

Patient and staff response

The pilot was immediately welcomed by patients and carers as an effective and user-friendly means for patients to access their own clinical information. They felt empowered by it. The most frequent aspiration was that it should include more data, and letters.

Immediate release of results did not lead to panic. A patient at a later meeting (paraphrased) “It’s still bad news, whether you tell me on a phone call or whether I find it out first. I’d rather get over the shock and discuss it later”. A clinician recounted “If a patient has a potassium of 7.0 and calls us before we have been able to contact them, surely that’s a good thing?” Presumably some anxious patients didn’t enrol, or deliberately didn’t check online (“I know they’ll contact me if it’s worrying”).

There were some staff concerns that access would generate anxiety, and increase demand for communication with patients between clinic visits, which would be hard to sustain. The opposite was usually described; the number of calls seeking results fell, and calls about results seen online were few, and mostly justified. Patients felt empowered and came to consultations better prepared. Time at appointments could be spent discussing the future rather than detailing results from last time. Clinician time seemed better spent.

Expansion and sustainable funding

On the back of these findings RPV steadily grew to full national coverage as technical links with all renal unit IT systems were established. Originally offered to those receiving dialysis or with transplants, its application expanded to all patients with information held on renal unit IT systems.

On the back of these findings RPV steadily grew to full national coverage as technical links with all renal unit IT systems were established. Originally offered to those receiving dialysis or with transplants, its application expanded to all patients with information held on renal unit IT systems.

In 2008 a sustainable technical and governance future for RPV was secured by co-locating its administrative support in the Registry offices. A capitation funding model was agreed – initially £2.50 per RRT patient for every unit in England where patients used RPV. Growth was rapid – by 2009 there were already 10,000 RPV users. The RPV committee, vigorously led by Turner and Simpson, continued to improve the interface and increase its functionality. The charge to units for the service was held steady.

Image shows RPV centres in May 2013.

Improvement and further features

A major software rewrite in 2014 made the application mobile-friendly and more scalable, and introduced the possibility of application to other specialisms. By 2018 added capabilities (incuding activity before and after the software rewrite) included

- Letters about you written from your renal unit

- Graphs to show changes in results over time

- ‘News’ functionality to update on changes or issues

- A smartphone app that included notifications of new results and other information

- Secure messaging between patients and professionals (e.g. to clinicians, dietitians, specialist nurses)

- Medication lists from units able to send current prescribing

- In Scotland, GP prescribing was also shown

- Detailed access logs showing activity of any user

- Patients could belong to multiple ‘groups’, e.g. a transplant centre as well as their local renal unit, but also to a special group constructed for a disease, or for a specific research project

- Ability to conduct questionnaires through the system. These could be targeted to all patients, or to specific groups (specific units, or other types of group)

- Re-routing of data to travel via a UK Renal Data Consortium at the UK Renal Registry. This enriched the information received by the Registry, and facilitated research projects such as RaDaR (see below)

A change of name to simply PatientView was made in 2014, as the system was tentatively being offered to other specialties. It was first taken up for inflammatory bowel disease, but the Renal Association was not enthusiastic about becoming a wider provider of such services.

The basis of information provision to RaDaR

A major part of the impressive power of RaDaR comes from its live connection to the dataflow constructed for PatientView. Transfer of data to RaDaR required (and continues to require) a specific consent step. The story of RaDaR is told here.

Handover and conclusion

PatientView had around 70,000 registrants by 2020. The PatientView responsibility for showing patients their results was handed to an external company PatientsKnowBest (PKB) following an agreement in 2020 (UK Kidney Association news). Units were migrated to the new provider over the following two years.

PatientView was a unique development. On the back of the renal profession’s extensive innovation in electronic records and registries of data comparing different regions, it added patient access and involvement in planning. These innovations were well in advance of other specialties, and indeed in the UK such advances have been only patchily achieved for other services more than 20 years later.

Further info

- Bartlett C, K Simpson, AN Turner 2012 Patient access to complex chronic disease records on the Internet. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 12:87. Describes the early set up and evaluation of Renal PatientView

- Phelps RG et al, 2014. Patients continuing use of an online health record: a quantitative evaluation of 14,000 years of patient data. Journal of Medical Internet Research 14;16(10):e241

Authorship

First published 2023

Last Updated on July 20, 2025 by neilturn